“Salaam Alekum, Abubakar, how are you?” I said as Abubakar answers my phone call. “Alekum Salaam, I am fine,” he responds cheerfully, “I am healthy and alive. Are you safe and okay? I heard that COVID-19 cases are increasing in the area where you live!” I was calling to check in on Abubakar and his community, but the conversation immediately turned to him checking up on me. The selflessness and gallantry of the communities in Kwale County in Kenya is something I have become accustomed to.

In my role at Blue Ventures, I support our partner organisations in Kenya in marine resource management. In Kwale County, the southernmost coastal county in Kenya on the border of Tanzania, these efforts are facilitated through our partner, COMRED. An integral part of my role is to connect with local communities to make sure our presence is felt throughout the partnership. Inevitably, the COVID-19 pandemic has restricted these connections to just phone calls, but poor signal and frequent power outages means it can take several days before I am able to reach someone by phone – a challenge that myself and my colleagues around the world are having to learn to adapt to.

Before COVID-19, the communities in Wasini relied on running boat safaris for tourists | Photo: Agatha Ogada

Abubakar is one of the many community members that I have built a strong bond with over the past few years. He is actively involved in the management of the Wasini no take zone in the locally managed marine area (LMMA). As the situation has worsened in Kenya, maintaining connections with community members like Abubakar has never been more important; our frequent phone calls have become the only way for me to learn how communities are being impacted by the pandemic.

“What is the situation in Wasini right now?” I asked Abubakar, “Well right now all of our tourism-related businesses are closed, which as you know makes up 80% of our livelihood,” he replied.

As soon as COVID-19 was categorised as a pandemic, the Kenyan government was swift to set up containment measures. The measures included 1.5 metre social distancing at all times, working from home for non-essential workers, mandatory wearing of face masks, a dusk to dawn (7pm – 5am) curfew and partial lockdown of some areas. When speaking to community members about the new measures, I soon learned that they are already posing numerous challenges, aside from the obvious lack of income opportunities as a result of the now non-existent tourism industry. Mtengo Omar, the chairman of Mkwiro Beach Management Unit (BMU) told me:

Getting service in the health centre is increasingly difficult – the doctors and nurses are scared to treat people because they do not want to risk exposure to the virus. Moreover, people are required to wear face masks which costs money. Money we don’t have.”

When I asked Abubakar for his thoughts on the government’s response he said, “I really commend the government for the handwashing campaign, it is something we as community leaders advocate for and encourage”. But he doesn’t sound very pleased, after a short pause, he adds, “However, in this pandemic, with no income, it will be difficult to keep up… If we have to buy soap and water with our savings to follow the government’s advice, how will we sustain ourselves?” These words struck a nerve, I can offer my moral support, but mostly, I feel helpless. My response is a meek, “Yes, I hear you”. Abubakar continues:

We are blessed to have the ocean, at least my family will have fish to eat. We are still figuring out how best to cope as we take it a day at a time.”

As is prevalent across East Africa, fishing communities in Kenya have been some of the hardest hit by the pandemic. The lockdown of three coastal counties (Kilifi, Mombasa and Kwale) has decimated the small-scale fisheries sector. As people struggle to find work, many have turned to the ocean as a source of food for their families, as Abubakar tells me:

This pandemic has turned everyone in the village to fishing. It is the main source of food and income for many people. The sea is now the only escape, we cannot run to Zanzibar, fishing is now our only way to cope… But this is of course dwindling our resources. We can only hope that the resources will have the ability to regenerate.”

Whilst the ocean is providing a short-term solution, this increased fishing pressure is problematic for efforts to rebuild struggling fisheries in the region. The curfew means night fishing is prohibited, so fishers who would normally fish in deeper waters have turned to the shallow areas for their catch, including the areas where we are actively trying to protect fisheries – the LMMAs. My conversation with Mwakiraa Mohamed, a Vanga BMU executive member, paints a sad picture of the impact of these measures:

They have cut and taken the buoys we put to mark our LMMA area. It is now a prime fishing area and there is not much we can do. The number of people fishing at the reefs here has increased but the fish trade has fallen very low. Previously here in Vanga, up to six fish trucks would come everyday to collect fish for the Mombasa and Nairobi market. But recently, only one truck has been able to ferry fish to Mombasa, and that was for the local market.”

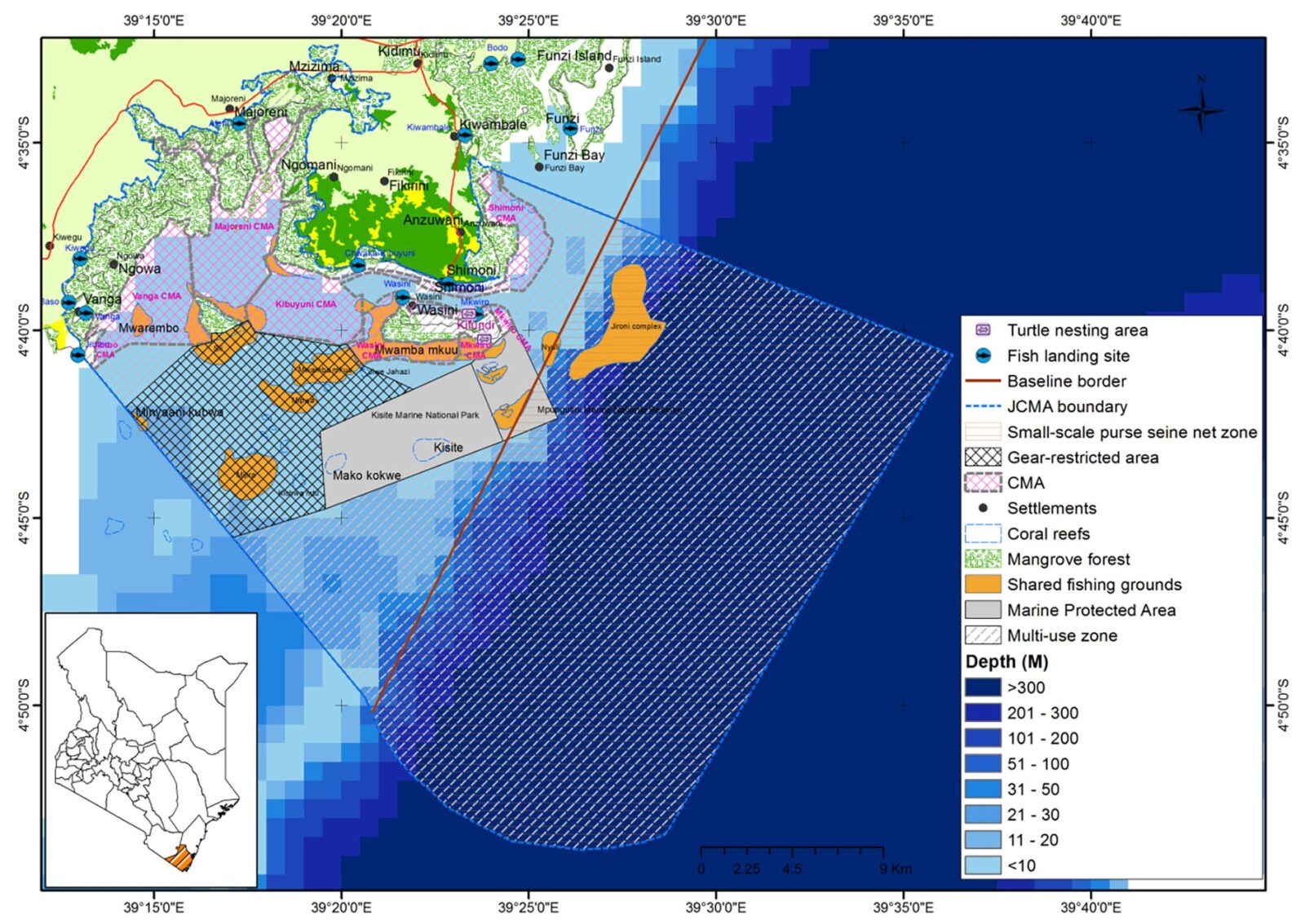

The map shows the protected areas which are now under fishing pressure due to the knock-on impacts of COVID-19

As Mwakiraa describes, the restriction of movement between counties has caused the fish trade between them to grind to a halt. Despite this, the demand remains high amongst local communities as they turn to fish as a staple food source. Mzee Omar Juma, a former Wasini BMU leader who now helps the BMU manage their LMMA focused projects, feels that there are reasons for some to celebrate the impact of the falling fish trade:

The price of fish was much more affordable during Ramadan this year. A kilo of fish selling at ksh 250($2.50) down from ksh 450 ($4.50) is a blessing for the poor in the village who now can now afford to eat more fish.”

Whilst Mzee is right, his words also strengthen the case for furthering community-led conservation efforts in coastal Kenya – these communities rely so heavily upon the ocean, particularly at times of crisis. It is vital that we continue to support locally-led conservation initiatives and build resilience to local, regional and global crises, so that future generations aren’t left with nothing.

Small-scale fishing is a vital livelihood for coastal communities in Kenya | Photo: Duncan Ndotono (Northern Rangelands Trust)

COVID-19 is an enigma. We are not sure exactly what it is but what we have seen is how deadly it can be. In Kenya, I have heard first hand accounts of how quickly it can tear through economies – our tourism industry is almost non-existent, with tour operators using their boats in desperation and fishing what are already depleted fish stocks. This is having a knock-on effect on the small-scale fishing industry, and is therefore hugely impacting the communities with whom we work; my role of supporting them has never been more urgent.

Based on the conversations I have had so far, Blue Ventures and COMRED are already making plans to re-establish presence (with precautions) in the villages to evaluate our fisheries management activities once the restrictions are lifted. At times the communities’ stories have been difficult to hear, but it is critical that we listen and understand their reality so that in collaboration with our partners, we can mobilise and decide how best to support them.

Blue Ventures is supporting our partner COMRED to deliver materials and awareness raising publications to help them to support the communities of Kwale County through this pandemic. Both organisations will continue to help these same communities rebuild their coastal fisheries in the long term.

Nice article that captures local voices in Kenya’s coast. COVID-19 brings large-scale uncertainties and impacts not previously thought about. The big question is how long this restrictions will last, and what will be the shape of the resource curve, not just the COVID-19 curve.

Great effort indeed. Well informed by the article. Please reach out to stakeholders to see how best they can address the problem at hand.

Thanks for an interesting and informative article. The impact of COVID-19 in fisheries is something we are seeing around the world.